|

Resource Identification for a

Biological Collection Information Service in Europe Results of the Concerted Action Project |

|

Resource Identification for a

Biological Collection Information Service in Europe Results of the Concerted Action Project |

[Contents] [BioCISE Home | The Survey | Collection catalogue | Software | Standards and Models]

Andrea Hahn

Pp. 39-48 in: Berendsohn, W. G. (ed.), Resource Identification for a Biological Collection Information Service in Europe (BioCISE). - Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin-Dahlem, Dept. of Biodiversity Informatics.

Execution of the survey. Devising the questionnaires (in English, French, and German), implementation of on-line forms, address list creation, the distribution of the questionnaires, data entry in the collection database, and the ensuing communication with data providers to clarify data content presented a major workload for the project secretariat, which was aided by project partners who organized meetings or individually distributed questionnaires. In some cases (principally major natural history museums), a personal visit by the co-ordinator was necessary to clarify the aims of the project and to obtain the data. As far as possible, collections that were known to already participate in functioning European networks of collection information were exempted from the circulation of questionnaires. This refers chiefly to zoological gardens and to collections of plant and animal genetic resources.

Mailing of questionnaires started in February 1998, and continued until July 1999, with a total of over 2500 sets of questionnaires mailed directly to collection holders. Electronic communication was gaining importance throughout the project period; about 70% of the responding collections provided an email address, which greatly eased follow-up inquiries. The updated questionnaires continue to be available through the WWW site in English, French and German. Care was taken to obtain explicit consent of the data provider for the publication of information on the WWW - most collections gave permission to fully publish their data.

A total of 413 professional societies and organisations were contacted and asked to support the survey by notifying their membership, by linking to the project's site through the WWW, or by publishing the call for co-operation in their newsletter or journal. This represented part of a continuous process of alerting the communities of collection holders to the presence of the project, to inform about its aims, and to iron out misconceptions. Oral presentations, an extensive correspondence and numerous personal contacts to promote the idea of the survey and raise awareness of its importance were other approaches taken by project members and the secretariat.

Impediments. The survey had to overcome several hurdles to get a response from collection holders. Many research collections, particularly those held in conjunction with ecological, chemical, or pharmaceutical research, are very difficult to identify and contact in the first place. In identified collection-holding organizations, the questionnaires often did not reach the appropriate person due to administrative obstacles. Also, potential respondents may not have realized the change in the scope of the survey mentioned above. The questionnaires were available only in English, French, and German, so that language problems may have de-motivated some potential respondents. Due to the fragmentation of the community of collection holders (see box on p. 3), the usefulness of a common access service is not necessarily obvious to all. Last not least, a general weariness of questionnaires had a negative impact.

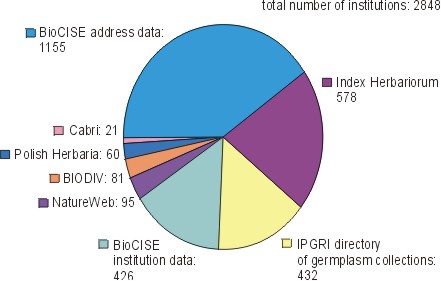

Figure 4: Collections in the BioCISE catalogue

Comprehensiveness. Our current rough estimate is that the project has contacted (directly or indirectly) about 75% of the collections which eventually could become part of a European service, estimated at a total of above 4000 (only collections accessible to the public, not including commercial nurseries and pet breeders). In spite of the difficulties mentioned above, the initial response rate of about 11% was increased to a final result of 19%, i.e. 484 replies.

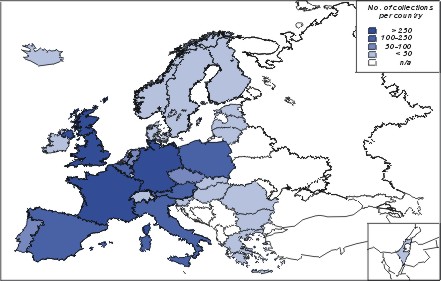

Figure 5: Geographical distribution of respondents

Figure 4 depicts the total representation of collections in the BioCISE collection catalogue, i.e. including verified address data and collections in linked networks (see Chapter X). Apparent differences in the number of collection-holding institutions per country (fig. 5) in the BioCISE catalogue may not always reflect the actual situation. Most non EU-members are not properly represented, because they have been included at a rather late stage of the survey (Poland is an exception due to the workshop held there). In some cases, like Iceland or Israel, the given numbers are probably representative, while for example in the case of Italy, with its long tradition in natural history research, language problems may have caused a relatively low impact of the questionnaires (though partly compensated for by a national workshop in Italian language). The comparatively high response rate in Germany demonstrates the importance of the immediate contact, which was confirmed by the increase of responses attained by means of national workshops in Israel, Portugal, Italy and Poland. Institutes are much more likely to respond to a survey conducted on the national level, and non-respondents can be traced more easily when they are located in the same country (however, in some cases the background of a European initiative certainly helped to attract response). One of the implications was the incorporation of a system of National Nodes at the core of the concept for the Information Service (see Chapter XI).

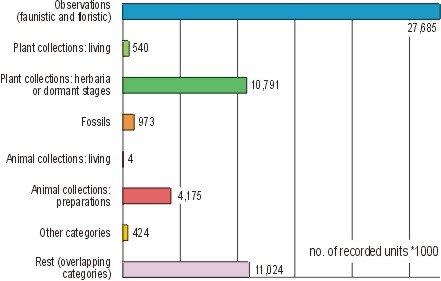

Figure 6: Collection units in respondents' databases

484 laboratories answered the questionnaires in detail. Of the respondents, 292 (60%) do maintain one or more biological collection databases. The total number of collection units (including survey records) catalogued in these 448 databases exceeds 42 million. Fig. 6 gives an idea of the subject areas covered. The bulk of units are records in floristic and faunistic mapping projects - these are mostly electronic records to start with. In contrast, most natural history collections are only starting to register their objects in electronic inventories. Although 42 million units looks like an impressive number, it must be compared to the total number held.

The actual number of objects and observations held by European collections is unknown. The results of the survey, together with some other studies, can be used to attempt some rough estimates. There are approximately 620 zoological living collections in Europe, including zoological gardens, aquaria, and animal genetic resource collections. According to our results and the information gathered from ISIS (ISIS 1999) and the Global Zoo Directory (Swengal undated), a total of about 800,000 units seems a reasonable estimate. Our idea of the number of objects in natural history collections is less exact. Global holdings of natural history specimens have been estimated at 2.5 billion (Duckworth & al. 1993), a number that may be realistic when all private holdings are considered. European facilities should hold a substantial, if not the major part of these. The very large facilities often have only a rather vague idea about their holdings. According to Naumann & Greuter (1997), the estimated number of zoological samples in natural history collections in Germany ranges between 50 and 80 million for invertebrates alone; the natural history museums in London, Vienna, and Brussels combine holdings of more than 50 million invertebrate samples; for vertebrates, numbers are given with 2.7 million for the decentralised German collections, while in Britain and France the large taxonomic facilities (Paris: 1.5 Mio, London: 5.5 Mio specimens) are likely to own the bulk of the respective national holdings.

The number of zoological observation records is even harder to assess. A number of zoological observation databases cover from 1 to more than 2.5 million records each, giving an indication of the soaring total to be expected from all over Europe. Examples include the Austrian invertebrate survey database ZOBODAT at the Biologiezentrum des Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseums, Linz/Austria, the database on migratory birds at the Bird Migration Research Station, Choczewo/Poland, the data collections on ringing recoveries and vertebrate mappings at the Zoological Museum of the University of Copenhagen/Denmark, and the butterfly observation database of De Vlinderstichting - Dutch Butterfly Conservation Wageningen/The Netherlands. The central database of plant observations in Germany alone holds more than 15 million entries, similar databases exist in other European countries, feeding their results (as presence/absence data) into the Atlas Flora Europaea project located in Helsinki.

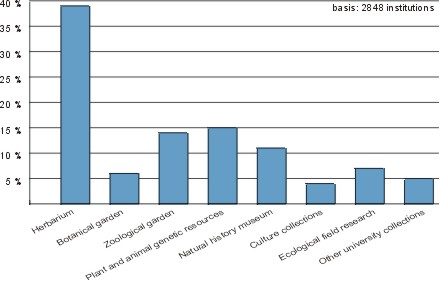

Figure 7 attempts a rough categorization of the collections accessible through the BioCISE catalogue (which includes data from linked networks and verified addresses of collection holders). The survey's supplementary function with relation to existing community networking activities and in preparation of inter-community collaboration must be considered when interpreting the results.

The coverage of herbaria should be more or less complete, thanks to the combination of survey data and linking through to the Index Herbariorum database (Holmgren & Holmgren 2000). Botanical garden coverage is also rather comprehensive, due to the excellent base offered by the Index compiled by Heywood et al. (1990). In contrast, only about half of the zoological gardens existing in Europe can be found in the collection catalogue, because those covered by the International Species Information System (ISIS 1999) are not included.

Figure 7: Collection categories in the BioCISE collection catalogue

We assume that the representation of plant and animal genetic resources (agriculture, horticulture, silviculture, breeding and fisheries) is less complete. Commercial nurseries have been excluded, but the distinction between, say, a commercial nursery and a horticultural research collection is arbitrary. For example, there are many commercial nurseries (as well as private persons) among the 425 collection holders recently listed in the British National Plant Collections Directory (Cook 2000) as owners of exemplary collections of garden plants. We also believe that many university departments hold reference collections, but we have had few contacts. However, joining forces with a well-organised international network (International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, IPGRI, see Chapter X) has increased the cover considerably, at least for plants.

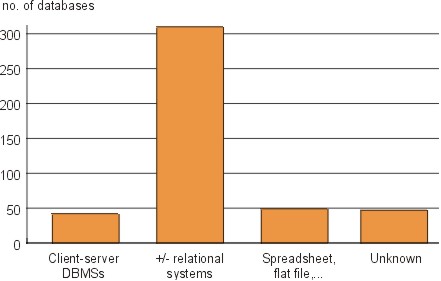

Figure 8: Database management system representation in the BioCISE survey

Collection holding facilities, which would call themselves a "culture collection" or a "Natural history museum", are well covered. However, the collection's content does not differ if the holder is a private person or a university department, both of which would not be called so. Especially with culture collections, there is the additional complication of biotechnology companies holding collections that are not advertised. Nevertheless, we think that many collections that fulfil the criterion to be publicly accessible in some way are not yet represented in the catalogue. This is also true for the remaining two categories. Many ecological surveys and reference collections are hidden in government agencies and private consultancies, and many university departments hold a variety of collections for teaching or reference purposes (e.g. oceanographic institutes holding microbial strains from deep-sea explorations, algae and collections of aquatic animals).

The results of the survey confirm that an increasing number of collections are computerised, with a widely varying degree of sophistication. The high number of different software solutions in use for the capture of biological collection data - more than 60 different applications were named for the management of collections in just about 300 institutions - reflects the heterogeneity of the biological community, the fragmented institutional base, and the lack of commercial solutions. Only 12% of the databases were developed in some kind of collaboration with other collection holders, but about 27% of the institutes reported to have some kind of internal IT co-ordinating body. About two thirds of database owners reported their solution to be developed in-house. Stand-alone (more or less) relational systems are clearly favoured, as shown in fig. 8, with MS Access (44%) most prevalent, followed by dBase (25%). More basic systems include "flat" structures using word processing files and spreadsheet tables. Larger databases are using client-server applications, here the majority (70%) named Oracle as their database management system. Of the 390 databases for which the relevant survey question was answered, 62% were developed in-house, 24% by external service providers, the rest in co-operation with other collection holders.

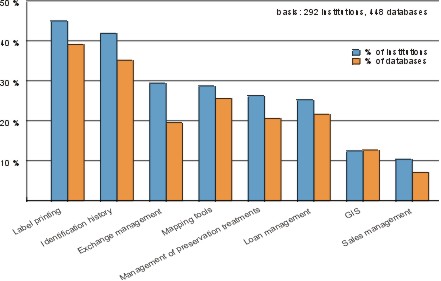

Fig. 9 shows the main features of collection database systems in use. The presence or absence of these features was explicitly asked for in the database questionnaire, so that the numbers should be representative for the overall functionality of programs in use. As apparent from the lack of administrative features (label printing, loan and exchange management), more than half of the databases encountered are more or less restricted to the task of simple cataloguing of existing collections. Among the more elaborate systems, the automated printing of labels from the information system and the documentation of a specimen's identification history were the most common features. Those with additional geographical information processing (GIS integration, mapping tools, point location) are fewer.

The questionnaires also asked for features missed by users, and these geo-referencing tools were topmost on the wish list; followed by on-line accessibility and interconnection with other databases. Complaints about missing administrative features (loan, exchange, and sales management) and label printing were less frequent.

On-line accessibility. Among the 483 collection-holding facilities responding to the questionnaire, 60 % had no on-line presence whatsoever before BioCISE published their data in the catalogue. Only 8 % offer unit-level information (i.e. data about individual specimens or observations of plants or animals in the field), while the remainder publish more or less detailed descriptive metadata on the content of their holdings. Since the survey was biased towards databased collections, and since the addresses of collections present on the web are much easier to access, the percentage of collections offering unit data is likely to be lower if all collections are considered. In animal collections, general web representation is slightly more common, largely caused by the web presence of natural history museums.

Figure 9: Principal features of respondents' collection databases

The questionnaire contained a subset of questions regarding expertise and willingness to co-operate. More than 10% of the participants (52 institutions) have offered to share their professional expertise with others, e.g. by reviewing funding proposals or by offering advice or practical support in the building of collection information systems. Fields of expertise named include WWW design, database programming, and geographic information systems. This is an encouraging sign for cross-community collaboration and mutual support, which will be drawn upon in the design phase of the common collection information service (Chapter XI).

Despite the difficulties encountered, the execution of the survey has been a central element in the BioCISE resource identification process. Without the contribution of BioCISE's own data, collaboration with networks (see Chapter X) would not have been possible. The survey has clearly demonstrated the importance of taking a community-oriented approach, be it oriented along thematic or national lines. It has led to the incorporation of a strong network of national nodes in the concept of the future service (see Chapter XI). The data gathered in the survey depict the heterogeneous state of biological collection databasing in Europe. The number of collection holders who were willing to fill in the rather tedious questionnaires are an encouraging sign for the strong interest in collaboration among European biological collections.

© BioCISE Secretariat. Email: biocise@, FAX: +49 (30) 841729-55

Address: Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem (BGBM), Freie

Universität Berlin, Königin-Luise-Str. 6-8, D-14195 Berlin, Germany